PaperMan1

The Paper Man

PaperMan1

The Paper Man

Prologue

When 20,000 people turn out to watch a funeral procession wind slowly through the center of a major city it’s safe to assume the deceased is someone fairly important. Yet the crowds that lined the streets of Vienna one cold, bleak day in January 1939 were not paying silent tribute to royalty, nor were they marking the passing of a major political figure. It was someone far more important.

The man being laid to rest in the center of one of Europe’s most elegant cities that day was a soccer player. He was the pre-war Pelé, star of one of the finest national teams ever assembled, a man who introduced the world to a caliber of of soccer beyond anything previously witnessed, dribbling past bewildered opponents as if they belonged to an earlier era. Poets sang his praises. His exceptional ability made him the idol of factory workers and café society intellectuals alike.

He would go on to become an unlikely symbol of resistance in a Nazi occupied nation.

Some say that he fired the first shot of World War II.

His name was Matthias Sindelar. This is his story...

PaperMan2

PaperMan2

Desperate Beginnings

Matthias Sindelar came from nothing. The son of Czech immigrants, he moved with his family to Vienna at age 5 so that his father, a mason, could find employment in the brickworks of Favoriten. It was on the grimy streets of this poor, drab suburb in the years following the Great War that Sindelar learned the skills that would forever change the game he loved – a game that would ultimately take his life.

On an empty lot opposite his apartment, Sindelar had his first experience with the hard, stuffed balls known as “Fetzenlaberl”, which the street urchins employed as substitutes for real soccer balls. Although years of undernourishment had left him suffering from a weak constitution, Sindelar soon demonstrated a genius with his feet. It was above all his capacity to outsmart physically superior opponents through his masterful dribbling that turned him into a neighborhood star in the bitterly fought matches against the boys from rival streets.

From this cauldron of deprivation, a new style of soccer arose, which was characterized by technical refinement and a reliance on agility over brute force and power. By the 1930s, the world would come to revere this new style of soccer as the “Viennese School” – and Sindelar as its father.

Vienna

As the surviving capital of a defunct multinational empire, the Vienna of Sindelar’s youth was a city of remarkable ethnic, cultural, and political diversity. In 1913, Adolf Hitler, Leon Trotsky, Josip Broz Tito, Sigmund Freud and Joseph Stalin all lived within a few miles of each other in central Vienna. There was even a popular ditty sung at the time praising the tolerance of the Viennese:

The Christians, the Turks, the heathen and Jew

have dwelt here in ages old and new

harmoniously and without any strife

for everyone's entitled to live his own life.

Vienna at the time was also a place that took great pride in its artists, past and present. The seats of this vibrant culture were the city's ubiquitous, grand coffee houses. It was here that Sindelar’s athletic prowess would come to be described in terms usually reserved for great acting or musical performances – no small compliment in the city where Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms cut their teeth.

Defining Injuries

When Sindelar was 15, his father was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army and deployed to the Italian Front of the Great War, where he was soon killed in action. The young Sindelar took the loss hard, as did his widowed mother, who struggled to raise him alone by working as a washwoman. The experience also planted the seed of Sindelar’s lifelong distaste for war and politics.

Hope returned not long thereafter, however, when Sindelar was spotted by a talent scout while playing in the streets. He was recruited into FK Austria, a professional team with a reputation as the club of the Jewish middle classes, but before Sindelar could prove himself, he sustained a crippling knee injury, which required surgery.

Despite his doctor’s warning that a re-injury could prevent him from ever walking – let alone running – again, Sindelar returned to the pitch as soon as he was able. The lingering threat of re-injury would come to define his career in an unexpected way, forcing him to develop an evasive style of play that dovetailed with his already conflict-averse nature.

It was the combined effect of these two life-changing incidents that would put him on a collision course with world events and a mortal conflict which he could not avoid.

Birth of a Star

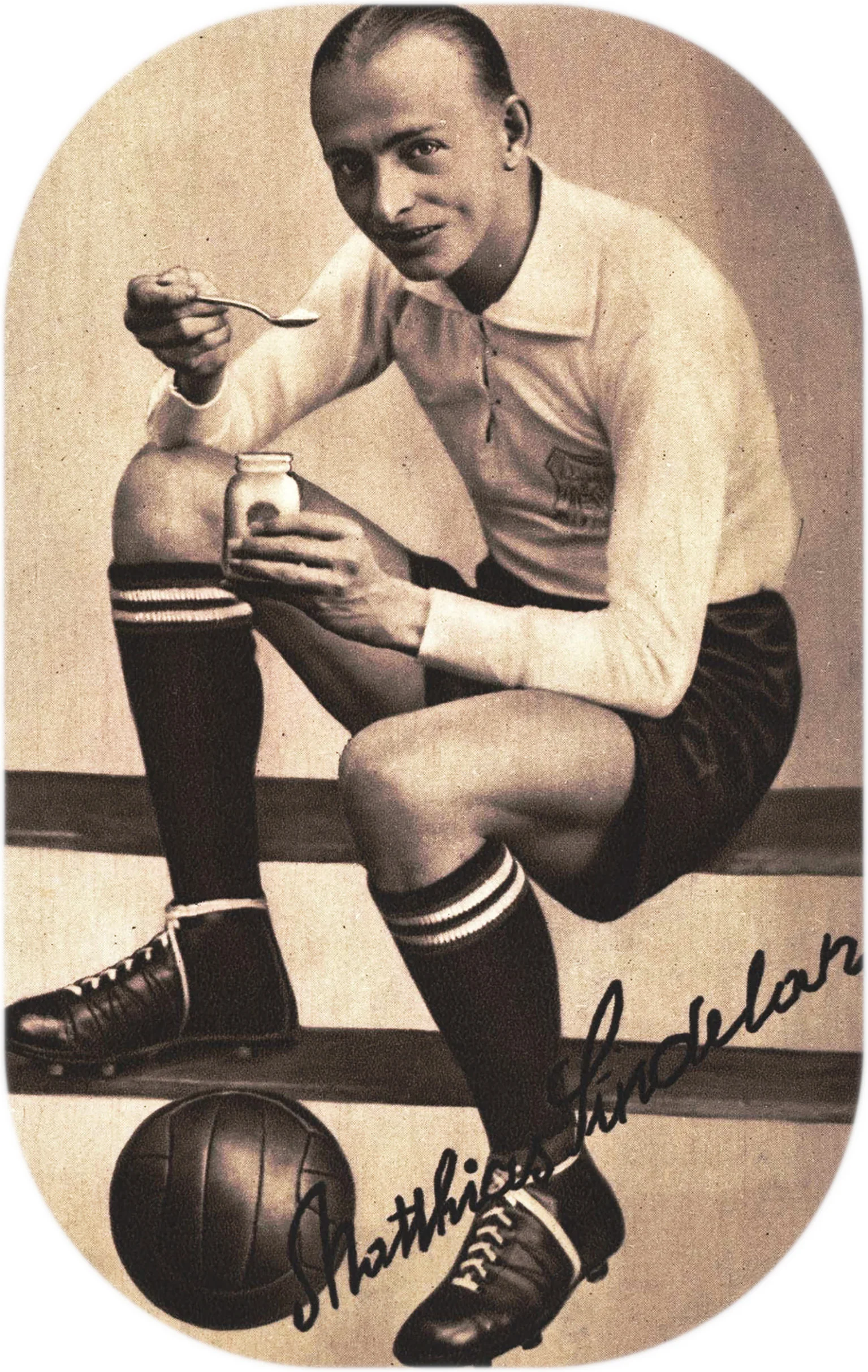

By the mid 1920’s, Sindelar had become the star of Austrian soccer. In his first three seasons with FK Austria, he guided the team to three Austrian Cup victories and a League Championship. Fans who saw him play would take notes. His importance in the development of the sport was colossal. An Austrian newspaper once commented that he played soccer “like a grandmaster plays chess”. Austrian journalist, intellectual, and theatre critic Alfred Polgar once said of him, “He had brains in his legs and many remarkable and unexpected things occurred to them while they were running”. Today, it is expected that a great attacking player be blessed with great vision and creativity, with the ability to unlock defenses, but this was not the case when Sindelar began playing. Soccer was a rough, aggressively physical game, and it took Matthias Sindelar to show the world that there was another way.

Sindelar also singlehandedly invented a position decades before it became commonplace. The second striker, or withdrawn striker – a type of forward who plays just off the front – has become a standard role on today’s squads. The position allowed Sindelar to have a greater influence upon the game, coming deep to receive the ball before conducting his team up the pitch like a symphony, and earning his second sobriquet, “the Mozart of football”.

Wunderteam

By the early ’30s, Austria had become arguably the best team in the world, earning the nickname “Wunderteam” in May 1931, when they demolished a strong Scotland side 5-0 in Vienna. The beautiful passing and lethal finishing displayed that day became a trademark.

In his book "Inverting the Pyramid”, Jonathan Wilson writes that “the modern way of understanding and discussing the game was invented in the coffee houses of Vienna, and in the realization of an aesthetic of Austrian football formed by their iconic forward Matthias Sindelar.” Coached by the revolutionary Hugo Meisl, who emphasized passing over power, the Austrians embodied an intelligent vision of the game that would be much imitated by opponents – a style that was regarded as artistic, even musical.

Following their rout of Scotland, the Austrians under Sindelar advanced unbeaten through their next 19 internationals, pushing 11 goals past Germany's goalkeeper in two matches with none conceded. All of Europe's top teams were toppled, and for the next three years, Austria dominated the world game.

Fever Pitch

Vienna, for its part, was swept up in a soccer fever like none before. In 1932, the city’s Prater Stadium sold out all of its 63,000 seats for a home match against Italy, whose roster included top stars such as Meazza and Ferraris and the South Americans Sansone and Orsi. Scalped tickets went for up to fifty times the normal price. Fans who couldn’t find tickets launched an assault on the stadium gates, and many were injured during altercations with the police. The Austrians prevailed after a hard-fought game, which saw Sindelar score one of the greatest goals of all time – a corner kick which he headed over one defender, then another, before nodding the ball past the keeper.

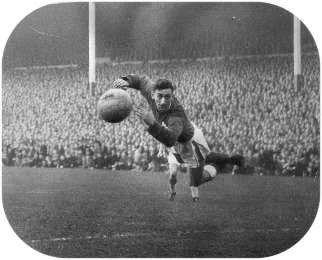

On the heels of their Italy showdown, the “Wunderteam” travelled to face down their most potent opponent: England. A sold-out crowd packed the stadium at Stamford Bridge, while an even bigger throng crammed into Vienna's Heldenplatz for the radio commentary. On the day of the big game, various factories and businesses in Vienna suspended work for the length of the match. The men’s clothing store “Unger” on the Landstraßer Hauptstraße offered a prize for every Austrian player who scored a goal. Thousands gathered to hear the soccer match in restaurants, cafes and cinemas, on soccer fields, in swimming pool facilities – even in open-air skating rinks. At the Parliament, the Finance Committee interrupted its meeting for the duration of the match.

It was proof that in the decade since the end of the Great War, soccer had developed into a true mass-cultural phenomenon. Years earlier, a mere 6,000 spectators had shown up in Vienna to see England pummel the Austrian team 6-1. This time, however, some 6,000 fans alone traveled from Austria and other continental countries to London to be present at the big event. The total combined attendance was 60,000, and at least 20 times that many gathered to hear the radio broadcasts in their home countries.

England took the match 4-3, but when the Austrians returned to Vienna, the reception awaiting them at the Westbanhof train station surpassed even their wildest imagination. Karl Sesta would later describe the scene: "It was like a black sea of swarming crowds. We had never seen anything like it, and we had seen a lot. Everyone wanted to shake our hands. It was a wonder that they didn’t tear the clothes right off of our backs. The police had their hands absolutely full escorting us through the crowd. I don’t think any one in all of Vienna worked on that day. They were so wild that they broke all of the windows on our bus.”

Celebrity

Along with that of his team, Sindelar's personal star continued to rise. The Times called Sindelar “one of the greatest players in the world”, while the Daily Mail described him as “a genius”.

Such was Sindelar's growing celebrity at home and abroad that he became a pioneering figure in sports endorsement deals, appearing in advertisements for sharp suits and luxury cars. Watchmakers advertised with slogans such as “Sindelar, the best player in the world, is the proud owner of a valuable Alpina-Gruen-Pentagon watch”. Riding high on his sudden fame, Sindelar gambled and womanized away much of his earnings.

When he received fantastic offers from English professional clubs – contracts that would have made him one of the highest paid players of his day – he rejected them, explaining that the British Empire already had enough world-class soccer players at its disposal, and that one more or one less would make no difference.

The truth was that Sindelar couldn’t bring himself to leave his homeland. And though economic hardship was starting to take hold across Europe, the Paper Man had yet to find out how difficult life could become.

More Than a Game

As the tide of populist nationalism began to rise, Europe's right-wing dictatorships pounced on the working man's sport as a means of drumming up support for their politics. Ironically, one thing Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco all shared before reaching the top was an indifference to the sport. But their rise to power was mirrored by soccer's ascent as a proxy arena for conflict between nations, and a way in which nationalist identities could be moulded and manipulated.

The first to exploit it was Mussolini, who embraced the game as a means of shoring up support for his fascist regime. He seized on Italy's hosting of the 1934 World Cup as a showcase for the re-birth of Italian power, drawing on the athletic imagery of the Roman Empire. At times, Italy appeared to have more sway than the official organizer, FIFA. Mussolini dictated which referees would oversee each match, and once on the field their behavior immediately led to talk of corruption.

The Austrians reached the semi-finals, where they faced an Italian home side keen to impress Mussolini. Heavy rain left the pitch a quagmire, which hampered the Austrians’ passing game, while Sindelar received some appalling treatment at the hands of Italian defender Luis Monti. He was one of the defenders humiliated by Sindelar’s heading trick two years earlier, and had told his manager Vittorio Pozzo: “When I see Sindelar, I see red.” A dirty kick early on left the Austrian striker limping for the rest of the game, but that didn’t stop Monti from delivering a final boot to Sindelar's gut in the final minutes of the game, while Sindelar was already sprawled in the mud. At one point, the referee, later revealed to have met with Il Duce alone before the match, actually headed the ball to an Italian player.

The Italians won by a single, disputed, offside goal, and Austria’s hopes of sealing their reputation with the Jules Rimet trophy were dashed. The match was an awakening for Sindelar. The game was no longer simply a game.

PaperMan3

PaperMan3

The Anschluss

Over the course of the past year, the Nazi Party had systematically eliminated all remaining opposition within the German government, and having consolidated his power as a bona fide dictator, Hitler turned his ambitions toward his German-speaking neighbor to the southeast. Shortly after the World Cup in 1934, the Austrian chancellor was assassinated in an attempted coup by Austrian Nazis, but while the coup failed, the writing was on the wall. In 1938, Hitler’s tanks rolled across the border unopposed to complete the Anschluss, or “connection” – a complete annexation of the Austrian state by Germany. Austria, renamed Ostmark, would constitute one part of a Greater Germany.

In spite of the mounting political turmoil in the 1930s, Vienna had retained its reputation as Europe’s cultural capital, but that fragile reality changed overnight. Hitler’s rolling mechanical behemoth flattened the artistic world of Vienna. Austrian art, music, political and social thinking, and, most of all, soccer, were subjugated under Nazi rule.

The newly formed National Socialist government wasted no time in disbanding the Austrian team, and Prater Stadium was requisitioned as a military barracks. Austria’s players were told that they were now citizens of Germany, and if their international careers were to continue, it would be as part of the German squad. Sindelar, single-minded as ever, outright refused to play for Germany, and this is where his story becomes legend.

A committed Social Democrat, Sindelar abhorred Nazism. As a prelude to the Holocaust, Austria’s Jewish players and officials were replaced. Some fled abroad, others remained in what would turn out to be a fatal decision. Jewish clubs were seized. The president of Sindelar’s Jewish-leaning FK Austria club was removed in favor of an “Aryan” replacement who forbade contact with Jewish players and replaced his predecessor’s portrait with one of Hitler.

PaperMan4

PaperMan4

New Reality

Over and over, the highest German authorities “requested” that Sindelar join their team, but each time he refused. It would have been easy for Sindelar, one of the most in-demand players in Europe, to take a job abroad, and he had influential friends in English soccer, but his next move was an unexpected twist.

In summer 1938, the “Grandmaster of Soccer”, even in his mid-thirties one of the most bankable players in the world, bought a scruffy street-corner cafe in his original Favoriten neighborhood and retired from soccer, turning his back on the game he loved. The cafe's previous owner, a Jewish acquaintance of Sindelar's named Leopold Drill, was being dispossessed by the Nazis – part of the ongoing legalized theft of Jewish-owned properties taking place throughout the city. Sindelar stepped in with a cash offer for the business, snatching it away from party bureaucrats, who couldn’t legally force a Gentile to sell. The deal done, the Paper Man slicked back his hair and quietly served beer and coffee to customers who had recently talked about him with awe and reverence.

Much of the run-down bar’s clientele was Jewish, and Sindelar soon attracted the attention of the feared Gestapo, which declared him “unsympathetic to the party”. Indeed, Sindelar had never hidden his political leanings and had insolently – and publicly – maintained close friendships with Jews throughout the Anschluss. Before long, the Nazi secret police were surveilling his every move.

PaperMan5

PaperMan5

Final Game

As an act of propaganda intended to demonstrate German superiority, a “reunification” match was arranged for in Vienna between the “old Austrian” side and the new Austro-German side. The Nazis billed the match as a celebration of ethnic German brotherhood. It proved to be one of the most extraordinary matches ever played.

Sindelar, still the country’s best player even at the age of 35, agreed to captain the Austrian side on the condition that they could wear their old Austrian red and white colors one more time. Knowing the match wouldn't be seen as valid without Sindelar's participation, the Nazis agreed, but on one condition – the Austrians were not allowed to score against the Germans, let alone win.

On April 3, 1938, weeks after the Nazis completed their annexation of Austria, the Wunderteam took to the field at Prater Stadium for the last time. In front of the 60,000 spectators crowding the stands, Sindelar slipped deftly though the German defense in classic Paper Man fashion over and over again, each time deliberately – almost comically – missing his shot. The crowd soon realized what was happening, and the match became a festival of anti-Nazism.

The play-acting continued into the second half. But then, at around 70 minutes, something snapped. Sindelar flicked a rebound from the German goalkeeper into the bottom right-hand corner of the net. The crowd erupted. Nazi functionaries looked on in disbelief as, soon after, Sesta slammed the ball into the German goal from 45 yards. 2-0. The crowd went wild.

At full time, the grim-faced Nazi dignitaries glared at Sindelar from the stands.

Death

On the morning of January 29, 1939, Matthias Sindelar was found dead in his apartment above the coffee house he had acquired the previous year, lying next to his comatose girlfriend, Camilla Castagnola. The official death verdict was accidental death by carbon monoxide poisoning.

The authorities claimed that the breakup of the team and city he loved had gradually forced Sindelar into depression, leading him to take his own life in a suicide pact with his half-Jewish girlfriend. But those who knew Sindelar knew better than to accept the official explanation. As if to confirm their suspicions, Camilla, still comatose from the poisoning, died suddenly after a mysterious visit from a man no one could identify.

Two days after Sindelar's death, the Viennese Kronen-Zeitung newspaper said, “all the evidence points to the fact that this splendid man, this model sportsman, was poisoned.” Matthias's sister insisted on keeping the investigation open, only to be told that since her brother was sympathetic towards the Jews, she must be too. Nazi authorities had the body buried before a thorough autopsy could be performed, then forcibly closed the police investigation after a few months. The files pertaining to the case soon disappeared, never to be recovered.

More than 20,000 people turned out for Sindelar's funeral. It was Vienna's first, and last, rally against their Nazi occupiers. Within a year, Europe's rivalries moved from the soccer field to the battlefield.

Every year on the anniversary of Sindelar’s death, past and present Austrian players gather at his grave to remember their greatest player...